“The invasion of non-local animals, such as the Asian Burmese python beginning now to populate the Florida Everglades, is one of the greatest environmental threats in the United States.”

– Steven Williams, Director, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

October 21, 2005 Homestead, Florida – Until recently, the top predator in the Florida Everglades has been the American alligator. The males can grow to nearly fifteen feet long and a couple of feet wide. The females are a little smaller, around ten feet. Their long teeth and claws are lethal weapons and their jaws are like steel traps. Nothing wanted to take them on until people started throwing their unwanted adult Burmese python “pet” snakes in the Everglades to get rid of the uncontrollable monsters which can grow to twenty feet long, or more. The python has a hinged jaw that allows it to swallow large prey after it has squeezed its victim to death. A small child is as vulnerable as a house cat.

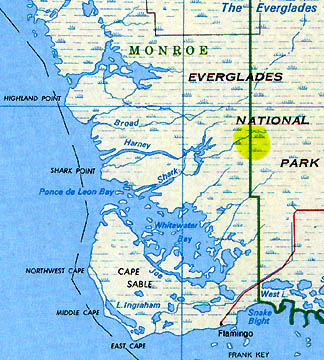

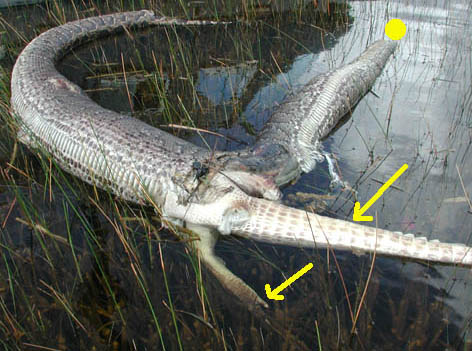

Since 2003. there have been at least four known python battles with American alligators. Two resulted in a draw and two seemed to favor the alligator. The last encounter was definitely a draw when both creatures died. That’s the photograph that went around the world in early October of a python body partially engulfing an alligator. The python’s head was missing and its belly seemed to have burst perhaps from indigestion after swallowing most, or all, of the alligator. The location was in the Shark Slough about 3 to 4 miles north, northwest of the Pay-hay-okee Overlook, which means “River of Grass” in Seminole Indian language. The remarkable scene was photographed the late afternon of September 26, 2005, by Everglades National Park helicopter pilot, Michael Barron.

Early the next morning on September 27th, Everglades National Park Wildlife Biologist, Skip Snow, went back to the scene with the pilot to do a floating necropsy in the waist-deep water. Originally, the two men had hoped to fly the python and alligator to a lab, but their flesh was too soft from decomposition after death. Some wondered if the alligator had been alive when it was swallowed and might have clawed its way out of the snake’s belly. But Skip Snow told me this week he found definite evidence that the 6.5-foot-long alligator had been inside the 13-foot-long python.

Interview:

Skip Snow, M. S., Wildlife Biologist, Everglades National Park, Homestead, Florida: “It was quite extraordinary. I had never seen anything like that. We had seen other encounters before, but certainly not one where we could confirm a snake had the alligator entirely within the digestive track which is what we deduced from looking at the intestinal tract. At one point, the alligator was indeed all the way inside the snake, but then for some reason that is not fully known, the side split and burst. So, here was sort of half alligator, half snake creature…

SO FROM YOUR POINT OF VIEW HAVING WORKED IN THE FLORIDA EVERGLADES FOR A LONG TIME, YOU HAD NEVER SEEN SOMETHING LIKE A PYTHON TRY TO EAT AN ALLIGATOR BEFORE?

No, we’ve never witnessed that. When I opened the snake, the tissue was quite soft. It was not too difficult to dissect the lower portion of it and the gut and see if the head and shoulders were still wrapped by the python’s stomach muscle. That was pretty clear that it had been in the digestive tract.

Missing Python’s Head

WHAT HAD HAPPENED TO THE PYTHON’S HEAD?

I don’t know for sure, but my best guess having looked at other carcasses especially in wetland systems or water once the carcass floats, is bloated and is floating, the head is denser and doesn’t float as well as the rest of the body and is the first to hang down in the water. I believe the absence of the head was post mortem after the snake’s death and probably was the result of scavenging turtles, some kinds of fish such as crayfish, and things like that which came and nibbled away at the head hanging down in the water.

It certainly was one of the most extraordinary things I’ve seen. More than that, underscored by the fact that here is this large, extraordinarily large predator that has never before occurred in the wild in the North American continent. Now we are faced with the fact that it’s breeding, it’s out in the wild, it almost borders on the absurd that I even have to deal with it! It’s now a condition of part of my job to have to consider what to do with this. It’s almost beyond thinking sometimes to look at this.

“Absurdity” of Burmese Pythons Let Loose in North America

THAT YOU ARE NOW HAVING TO DEAL WITH AN ASIAN BURMESE PYTHON IN ADDITION TO THE BIG AMERICAN ALLIGATOR.

The big alligator is not a problem. That’s a known because it’s a native here. The absurdity of it is the size and scale of this predatory animal being the python which has been introduced. And it’s really something “we” the human collective “we” have done to ourselves. It’s not like these snakes have stowed away and come over unbeknownst to us and made their way like an exotic flu virus. We did this to ourselves. We trade in these animals. We sell, we breed, we move animals about and within the pet trade at large, we always run the risk of this occurring. Now, it’s the extreme absurd end of it.

If you were to look at it as a willful act, thinking about how absurd it would be if someone came to me as a park biologist and proposed, ‘We should introduce tigers to the Everglades. It’s a large, predatory top-of-the-line animal. Let’s introduce tigers.’ Think how absurd that is. Well, it’s the same idea, just a different class of animal. But some days, that’s how it strikes me when I see encounters, things like this most recent incident. Part of me just thinks how absurd and I have to deal with it.

RIGHT. AND THAT THESE WERE BASICALLY THROWN AWAY PETS THAT BECAME TOO MUCH FOR THEIR OWNERS.

Yes. We believe for the most part is what we’re dealing with is a result of the number of years of intentional releases from unwanted pets. There is always the possibility that some have come as unintentional escapees or releases. But by and large, we feel that most of what we’re dealing with are results of pythons that have gotten too big. They have worn out their welcome, they’ve exceeded the economic ability of people who have owned them, or people have moved, or the spouses can no longer tolerate. Whatever the situation might be, these animals have been turned loose over time and now we’re faced with a breeding population.”

Breeding Burmese Pythons Threaten Everglade Ecosystem

Another scientist who has been working in the Everglades since the early 1970s is Frank Mazotti, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Wildlife Ecology at the University of Florida in Ft. Lauderdale. Prof. Mazotti is extremely alarmed at the rapidly spreading population of Burmese pythons that are not supposed to be in Florida, let alone North America. Nearly 200 Burmese pythons have been killed, or removed from, the Everglades since 2002. When their bellies have been opened in necropsies to see what the big snakes have been eating, endangered species have been found, including the beautiful White Ibis that the Everglades park has tried so hard to protect. Pythons also like to go after bird eggs. Dr. Mazotti points his finger at the exotic pet trade and says unless it is stopped or strongly curtailed, the Burmese python will continue to spread and wreak havoc on the Everglades ecology.

Frank Mazotti, Ph.D., Associate Prof. of Wildlife Ecology, University of Florida, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida: “Burmese pythons are incredibly popular in the pet trade because they are so easy to breed and because they have their mystique of being a python. So, it’s after all of these years repeated over and over again, getting more frequently, it really dramatically got everyone’s attention in the last two years.

IN JUST THE LAST TWO YEARS?

In just the first two years. You can look at the last 20 years and I’ll be you 90% of the pythons caught in the park certainly more than 80% – have been captured in the past 2 years. Part of that is because repeatedly letting go these pet snakes, boy snakes met girl snakes and now we’ve got baby snakes and now they are breeding. Once they started breeding, that’s when the numbers started skyrocketing.

HOW DO YOU THINK THIS RECENT BURMESE PYTHON ATTACKED THE ALLIGATOR IN THE FIRST PLACE? WOULD IT HAVE TRIED TO KILL IT FIRST BEFORE INGESTION?

Nobody has seen one of these fights start. What I think happens is that they both like the edges of wet and dry areas and that’s where they are likely to encounter each other. In one instance, it was in a small pool near a culvert underneath the road and the alligator was observed right after it had grabbed a python and the python was still alive. Under those circumstances though, the alligator was able to I think it was about an 8 foot alligator and 9 foot python. The alligator was able to subdue the python and swallow it after – it took awhile for the alligator to get the python down.

And then in 2004, on one of the park trails, a number of park visitors witnessed a battle between a python and an alligator that they don’t know how it ended, but the alligator swam away with the python in its jaws.

The 4th one was in 2003 and that was along another park trail and it was another battle encounter and in that circumstance, it looked like the alligator had won. But it let go of the python and the python swam away. There was no evidence that the python had died as a result of the encounter: that is, they did not find any bodies.

In one, the alligator clearly won. One where the alligator probably won. One that was a draw. And one where I guess there were two that were a draw. Because although the python swallowed the alligator, it does not look like the python was a winner in that one.

HOW DID THAT PYTHON LOSE ITS HEAD?

Probably another predator. It could even have been another alligator. It depends on how decomposed it was. After they start decomposing, turtles and crayfish and lots of smaller animals can get involved.

SO, IF WE HAD BEEN THERE WITH A HIDDEN CAMERA, WE MIGHT HAVE SEEN A STRUGGLE. THE SNAKE SOME HOW ENGORGES…

You might have seen a python attack an alligator, only to be subsequently attacked by a bigger alligator which would have I would like to be shopping around that footage.

AND THAT CONTRARY TO THE FIRST NEWS REPORTS, IF THE SNAKE HAD GOTTEN ITSELF AROUND THAT ALLIGATOR AND EVEN IF THE ALLIGATOR WAS HAVING THOSE REFLEXES OF CLAWING INSIDE THE SNAKE IT WAS NOT THAT THE ALLIGATOR GOT OUT OR THAT THE SNAKE EXPLODED?

That’s my I think that is the most likely scenario I’m going to give you a caveat here. That’s where the snake swallowed the alligator, doesn’t digest it, dies and they both start to decompose. But I would not call it an explosion. Say you have a balloon in your hand. It wouldn’t be a bang, it would be a fizz.

SORT OF LIKE THE TISSUE DETERIORATING AWAY.

Right, and all the gases start getting out in more of a puff than a bang. I think rupture would be a more accurate term than explode. But if you’re on the 6 o’clock news, the term ‘explode’ sounds a whole lot better.

Invasion of Non-Local Animals “Greatest Environmental Threat in United States”

STEVEN WILLIAMS, WHO IS DIRECTOR OF THE U. S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE, SAYS THAT THE INVASION OF NON-LOCAL ANIMALS SUCH AS THIS ASIAN BURMESE PYTHON BEGINNING NOW TO POPULATE THE FLORIDA EVERGLADES IS ‘ONE OF THE GREATEST ENVIRONMENTAL THREATS IN THE UNITED STATES.’ I WONDERED IF YOU COULD COMMENT ON HIS STATEMENT?

That is absolutely true. Almost everywhere you go, there is some non-native species that is causing major problems and costing lots of money for control. Certainly, right up there with loss of habitat and pollution. In fact, I would say that invasion by non-native species is biological pollution. And it’s just as deadly as the chemical kind.

WHAT IS THE WORST CASE WITH THIS POPULATION EXPLOSION OF BURMESE PYTHONS IN THE EVERGLADES?

The worst case is it’s going to have tremendous ecological impact as a top-down predator. Clearly, it’s staking a claim to be at least an equal to the alligator. That means it affects every other animal than it’s bigger than it can eat. It can compete with other native species such as Indigo snakes, which are endangered. Indigo snakes also get very large 7 to 8 feet. So, for a large part of its life, Indigo snakes will be competing with Burmese pythons for food.

THE BURMESE PYTHON CAN GET UP TO 20 TO 25 FEET.

And then they can start eating Indigo snakes. So, not only is it a competitor, but it’s a potential predator. One of the things that worries everybody about Burmese pythons is that they are very much a generalist in their diet. That means they will eat whatever is available. They eat mammals and birds and other reptiles. There are lots of endangered species in the Everglades, I think more endangered species in Florida than any other state except maybe California. If the pythons get established and they start eating everything, it could be a big problem.

WHAT YOU MEAN IS: IT’S ALMOST LIKE A MONSTER IN A MOVIE THAT IT IS POPULATING IN THE EVERGLADES -ORIGINATING FROM ASIA – AND CAN EAT JUST ABOUT ANYTHING THAT IT WANTS TO.

That’s correct. Since they get bigger than 20 feet, it’s pretty much (they can eat) what they want.

Human Children As Python Prey?

WHAT ABOUT THE VULNERABILITY OF CHILDREN?

Anything small is always the most vulnerable to a predator. Small children are more vulnerable to alligators and certainly it is no different to pythons. The size makes them attractive. The way they behave makes them attractive, walking down to the water’s edge and splashing around. You’re a python, you go yum! no hair.

What Can Be Done to Control Everglades Burmese Python Population Explosion?

WHAT IS IT THAT THE STATE OF FLORIDA OR FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ARE DOING NOW TO CONTROL THIS BURMESE PYTHON POPULATION EXPLOSION?

I think there are two critical steps that the state and federal governments need to engage in. One is to ask the question and hope answer it: what can we do to stop pythons being released? There is no control method that is going to be successful if people keep releasing pythons. That’s why we’re in this problem. We can’t keep doing it and hope to solve the problem. So, that’s the first step and that’s probably the responsibility of the state.

Then the second issue is: what are we going to do to get rid of the pythons that are out there already? I think it focuses on pythons in the Everglades National Park. I think what we need to do is have an integrated research and control methodology put into place so we start removing pythons that are out there, but at the same time, we learn how to do it better and smarter and less expensively.

HOW DO YOU THINK THAT SHOULD BE ACCOMPLISHED?

I think we need to follow very much the same procedures they followed in coming up with the control methods for plants, like Brazilian pepper. You need to understand how the animal makes a living. You need to understand what it’s vulnerable to. You need to understand where it lives, when it moves all the things that make your ability to traffic and remove the snakes more successful. Those are really on the top of the list of the information we need to have.

IF THEY ARE TRAPPED AND REMOVED, WHERE DO YOU TAKE THEM TO?

When you have a large non-native species like this, really almost your only alternative is to euthanize it. Nobody wants that’s why they let the snakes go in the first place. You might say, ‘Oh, I’ll get this python at 3 feet and grow it up to 12 feet and then I’ll donate it to a zoo.’ Zoos don’t want those animals. They have all the animals of that size that they need already. So it’s impossible to get rid of snakes those sizes. And one that has grown up in the wild will never become accustomed to humans so it’s never going to make a good pet. So, the regretful situation that we’re placed in is that we have to euthanize the snakes that we capture and remove.

SO BASICALLY THE ONLY PROGRAM IS CAPTURING THE PYTHONS AND KILLING THEM?

That’s correct.”

More Information:

Skip Snow is also working on control efforts: “There are a number of things we are trying to do to control the python spread. One is to ensure there are no more snakes released. So, the park is promoting a slogan and materials that revolve around the idea: ‘Don’t let it loose, be a responsible pet owner.’ We are trying to get people to consider that and find other alternatives other than releasing animals when they are no longer wanted. Plus, learn beforehand what they are getting into before they make those ‘pet’ purchases.

“We’re also working on ways to prove our ability to remove the animals that are here. That involves a couple of things. We have a proposal to try and adequately research and design effective traps which might be baited. We might use artificial lures in traps that could work in both flooded and dry land environments. Also, we are working on training dogs to sniff out pythons. A dog, or dogs, might alert us to the presence of pythons which we can then hand capture and remove. Dogs are used to sniff out exotic snakes such as the brown tree snake in Guam and Hawaii.”

Website:

National Park Service: http://www2.nature.nps.gov/YearinReview/02_B.html

© 1998 - 2024 by Linda Moulton Howe.

All Rights Reserved.